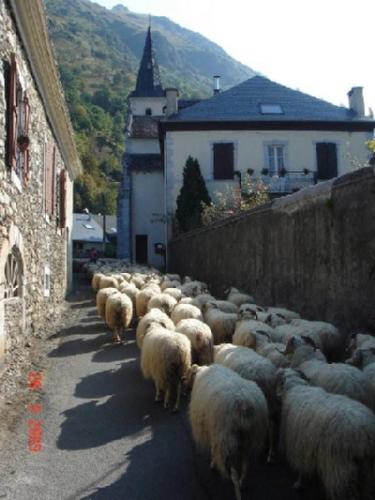

Transhumance, sheep’s cheese and pastoral life.

The Ossau Valley is a valley that has managed to preserve its pastoral way

Sheep’s cheese

Milking is mainly a series of daily tasks carried out to make cheese. These cheeses are the true fruits of passion which, held in the shepherd’s hands, emerge from the cauldron like newborn babies, carrying within them all the flavours and whims of the mountains.

Every day, the cold milk from the previous evening is mixed with the warm milk from the morning, collected in a large copper cauldron. Heated to 30°C, it is curdled by adding a few drops of rennet, a ferment derived from lamb rennet, and the milk slowly solidifies.

When it is firm enough, it is cut into grains with a “curd knife”. The curd is then gently stirred by hand and heated to 38°C to remove the whey. When this process is complete, the cheese grains settle at the bottom of the cauldron. This is where the cheese is born, as the grains are manually pressed into a ball, which is then placed in a mould to give it its final shape.

After being salted, the cheeses are matured for at least three months in cool, damp cellars where, under the care of a matureur who rubs and turns them regularly, they mature slowly and their taste and flavour develop.

Made from raw milk, the cheese is directly linked to the life, behaviour and diet of the flock. It tells the story of our culture and our mountains. It exudes the warm smell of hay in the sheepfold in winter, the growth of grass in spring, and the mountain pastures in summer, with their flavours of liquorice and wild thyme. It breathes the flowers that embellish the mountains in summer and the clear water of the streams where the sheep drink and the evening milk is cooled. It also expresses the passion of the shepherd and his land. The fruits of our culture, the gestures and methods of production are passed down and evolve from generation to generation. Cheese making dates back to the Neolithic period, when humans learned how to raise livestock and preserve food.

In the beginning, animals produced milk seasonally, and cheese was initially a way of preserving it for the whole year. Cheese comes from the East. It was in the Near East that man first domesticated sheep and goats and thus became a shepherd. In ancient mythology, milk and cheese were the food of gods and heroes. Milk, a true source of life, is the first food that promotes growth in children. This undoubtedly explains the importance and myth of the shepherd, symbol of life and fertility. Sheep’s cheese is a link between all the mountains of the Mediterranean basin. In our department, we are fortunate to have an AOC (Appellation d’Origine Contrôlée), a tool for all farms that live off sheep’s milk in the Basque Country and Béarn. The AOC must guarantee the future of our production system, which relies on local breeds capable of grazing in the mountains.

Only this system, which has shaped our identity, can maintain the high quality of our cheese, thereby ensuring a future for all the shepherds in the department and offering hope to young people who want to settle here. From the high pastures of Ossau to the ocean spray, Ossau-Iraty cheese is truly the fruit of a region crossed by several valleys where people with diverse cultures and skills live side by side. This diversity is an asset and a treasure that we must preserve. In the face of standardisation and increasingly draconian regulations, our cheeses are also a symbol of authenticity, a plea for all specific characteristics and for the right to be different.

Milking the ewes

At the end of December, it is time to sell the first lambs for the end-of-year celebrations and wean the ewe lambs that are kept for the renewal of the flock. This is the start of the sheep milking season, which ends eight months later in the mountains. Few in number at the beginning, the number of ewes to be milked increases as the season progresses and the lambs are sold in stages.

Milking is the highlight of the shepherd’s day, whose daily routine is closely linked to the life of the flock. It is an emotional and almost sensual relationship with the animals. Slowly, we tame the most skittish ewes, who run away when they see us but soon come closer to give us milk as soon as we enter the sheepfold. Milking means spending hours immersed in the heart of the flock; it means recognising all the ewes at first glance, or simply by touching their udders. It is there, in the intimacy of the flock, that we discover their characters and individual behaviours.

Even though it’s daily work that takes between three and six hours depending on the season, these moments of symbiosis with the flock always pass very quickly, especially in winter in the warm, hushed atmosphere of the sheepfold. This task becomes a chore in the persistent June rain, when the mud and damp cling to the animals and penetrate to the bone. In the mornings, when you are woken by the rain on the roof of the hut, you have to go and gather the herd, which is soaked and battered by the night’s rain, and milk them for two to three hours in this damp, cold atmosphere. It’s a real nightmare. Just as milking can become magical under the stars.

The sheepdog

Herding and guarding a flock of sheep in the mountains is completely impossible without a dog. A shepherd without a dog is like a naked king, totally powerless and unable to control a flock. The dog is an indispensable companion.

For me, the sheepdog is above all a gaze and a heart, two eyes in which you can feel the love, the complicity, the great pleasure of driving the flock and sharing these moments together. Our dog is a little Pyrenean sheepdog, a little ball of fur completely crazy about sheep and work, more passionate and impatient than us. It is a real pleasure to share her life and work with her; it is a true love story.

Shepherds in the Pyrenees have two types of dogs. The small shepherd, the “labrit”, a lively and intelligent animal that drives the flock, gathers it and brings it back… The large Pyrenean shepherd, the “patou”, is a livestock guard dog that has grown up with the lambs and has made the flock its territory and the sheep its friends, protecting them from any intrusion or attack from outside. Its sad eyes, tender gaze and gentle demeanour give it an harmless appearance. But don’t be fooled, it is a formidable animal, capable of deterring bears or wolves from attacking the flock and of rivaling any stray dog that wants to attack the ewes. If you see one in the middle of the flock, it is best to give it a wide berth, as it often does not tolerate the presence of strangers.

The birth of lambs

At the end of autumn, the ewes return to the sheepfold to eat hay, cereals and sleep in the warmth. Their bellies grow round and their udders swell disproportionately, full of promise. The flock must be moved with care, without running or exhausting the animals with long walks: lambing season is approaching. Gentleness must be the watchword for handling the flock and keeping them calm.

The first lambings in November are the result of artificial insemination carried out five months earlier in the mountains with the sheep centre. This method is used on the best ewes and improves the herd’s capabilities by taking advantage of the best rams in the department, selected by the sheep centre. Increasing milk production per ewe is first and foremost a passion for farmers, a desire to live better with fewer ewes and, especially today, a way of surviving with our flock in the face of the race for yield and productivity.

But for us mountain farmers, it also means being able to say and demonstrate that the mountains are not a handicap to modern farming; it means showing that we are producers in our own right. The first lambs born from insemination are precious. So in November, when we see one or more ewes that are going to lamb during the night, we keep watch in the evening or sleep in the sheepfold. The shepherd’s intervention is often essential to help with the birth.

The birth of lambs is always a moment of intense emotion, a happiness that is repeated each time we witness the miracle of life. When they are born, lambs are often clumsy: they need help suckling and drinking the first milk that will give them the strength to fend for themselves. The birth of the first ewe lambs, which are kept to renew the flock, brings with it the hope of more abundant harvests and is a precious gift for us, like a promise of more fruitful days ahead. In the sheepfold, the liveliness of the lambs jumping around after the calm of autumn is life reclaiming its rights and erasing the fatigue of sleepless nights.

The Shepherd

Summer: the mountains

Autumn: reunions

Winter: the lambs

Spring: milking

These are the four seasons of the shepherd.

Belly for dinner,

dry stones for walls,

tarpaulins for a roof,

close quarters in the hut,

such was the life of those who left the mountains.

Five thousand years ago, there were shepherds in our mountains and no cars. But we lost our “senior rights”.

As long as there are shepherds in sufficient numbers, the mountains will be maintained and beautiful…

As long as tradition, heritage and craftsmanship remain one, let’s continue…

When the first frosts arrive, the shepherd is alone in the mountains with his sheep.

And that is when it is at its most beautiful. He enjoys it alone…

When I am alone on my mountain, I think of all the shepherds around the world who are alone on theirs…

A vulture flies by… a marmot whistles…

a chamois escapes at the edge of the cliff…

a bear scratches itself on a tree…

a happy shepherd!

The Pyrenean Shepherd Dog is lively, intelligent, sociable, expressive, beautiful, tireless, sober, discreet and has an infallible instinct.

It would be difficult to find a master who resembles him.

A dog + a hut + sheep + a mountain x a little philosophy = happiness?

Our life as shepherds must be like friendship: shared to be lived.

If you pass by the shepherd’s hut, stop and come in. There will be two happy people.

And as Brel sang: we share bread and cheese, and for an hour we believe we are part of the shepherds’ journey….

by Daniel Casau